Major/minor boxes

The five pentatonic boxes, major and minor

We’ve spent a tremendous amount of effort covering the minor pentatonic scale because it’s the simplest and most generally useful scale for soloing. Again, the minor pentatonic scale works even over major chord progressions (with care) but the opposite is definitely not true. Major scales generally sound terrible over minor chords.

The huge majority of songs are written in major keys, however, so it’s time we learned how to play major pentatonic scales.

The good news is the box shapes are actually identical (just shifted down three frets)!

The bad news is that you must think about the notes within the shapes completely differently to use them effectively.

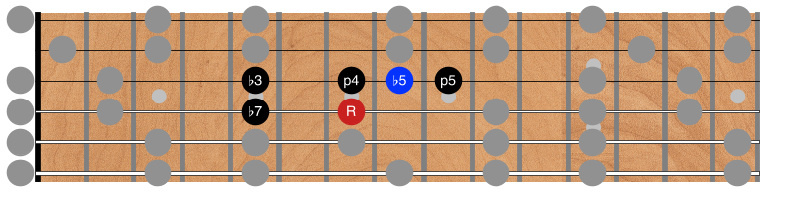

As covered previously, The minor pentatonic scale comprises the root, ♭3, P4, P5, and ♭7 scale degrees. In the key of Am, that’s the notes A, C, D, E, and G.

Diatonic theory taught us that every major scale (“Ionian mode”) has a relative minor (Aeolian mode) and vice versa.

In other words, the white keys on a piano can either be thought of as the C Major scale, or the A minor scale.

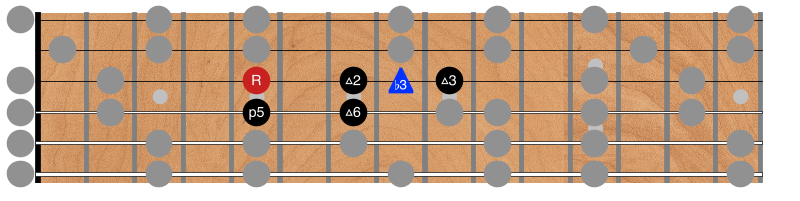

In the same way, the notes from the Am pentatonic scale are the same as the C Major pentatonic scale. The five notes C, D, E, G, and A now become the root, M2, M3, P5, and M6 of the Major pentatonic scale.

The same single octave “frying pan” we looked at earlier can be minor or major, depending on context:

Am-frying-pan.png

Fig 2. C Major "frying pan"

Note that the root is now located at the “toe” of the pan rather than the heel!

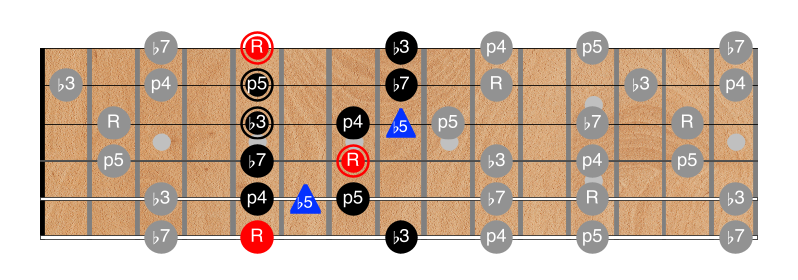

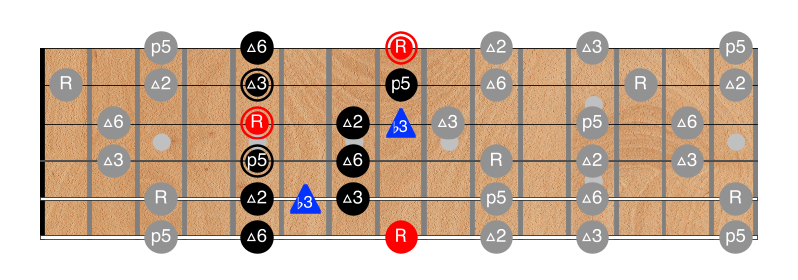

The same thing happens with multi-octave patters. Here’s “box 1” shown first as Am pentatonic, then as C Major pentatonic:

Fig 3. Am pentatonic box 1

Fig 4. C Major pentatonic box 1

It’s the same notes!

The shapes are identical, but the function of the notes changes.

Even the blue note is still the blue note. It now functions as a ♭3 instead of a ♭5!

Many books will tell you that you can form a major pentatonic “scale” (really a box-shaped fragment) by moving a minor pentatonic “box” three frets lower.

In other words, to play A major pentatonic, we could take the box 1 shape from figure 1 and move it down three frets. Alternately, to play C minor pentatonic, we could move it up three frets.

It’s not that simple, though, because you can’t just take the same minor licks and phrases you’ve been using for minor chords and use them in a major context. It’s vitally important to emphasize chord tones in your solo, the root in particular.

If you move box 1 down three frets and play the same licks, you’re going to emphasize F♯ and it’s going to sound like F♯ minor, not A major!

In particular, if you’re playing over a major chord, the M3 note will sound consonant, and the m3 will be dissonant. Playing the M3 over a minor chord is even worse!

That’s why I strongly recommend thinking of the major pentatonic scale as completely different from the minor pentatonic. That they happen to have the same box shapes is just an artifact of modal theory. You use them in utterly different ways.

While our fingers are already familiar with the box shapes, we still need to program our ears and brain to start “seeing” them in a major context rather than minor.

The five pentatonic boxes, major and minor