Blue note

If you’ve been following along with the proficiency tests, we briefly experimented with sounds outside the pentatonic scale by “curling” the m3, and by sliding into one of the five pentatonic notes from a fret above or below.

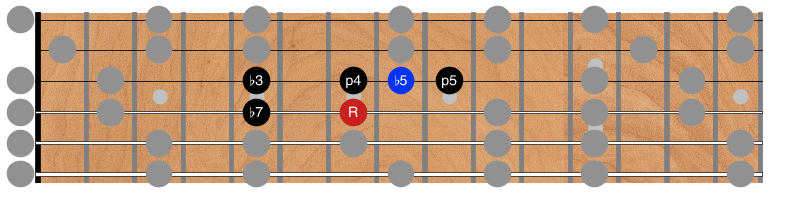

One of those “outside” notes (the ♭5) is so significant that it’s earned the name of “the blue note”. Adding this note to the minor pentatonic scale makes such a profound change that some people call this new six-note scale by another name: the blues scale:

Fig 1. The blues scale

The ♭5 is known as the “blue note.” It sits squarely between the tip of the handle and the base of the pan.

Start by using it wrong

Put on an Am backing track and try playing just the note E♭. Try different rhythms, but sound just that one note. Really hang on it.

Slowly add additional notes from the scale, but intentionally move back to the ♭5 from these new notes. In other words, end your lines on the ♭5.

Yuck!

You probably found that exercise difficult because it sounded so bad. Most people desperately want to move the final note in a line to any other note in the scale.

Blue note theory

The blue note adds such a tremendous amount of tension because it sits precisely in the middle of the scale, exactly six semitones away from the root note in either direction. It’s like balancing a see-saw: it desperately wants to fall in one direction or the other.Now fix the problem

Instead of making the blue note a destination that you end up on and hang out on for a while, try making it a note you move from. That is, move it earlier into a phrase, perhaps off the beat, and end up on one of the pentatonic notes nearby. In other words, use it as a passing note between other notes.

In particular, try playing the blue note, then hammering onto the P5 (again, over an Am backing track). Ahhhh! Doesn’t that sound great? It’s the sound of tension, followed by release. Try sliding down from ♭5 to P4. Try sliding between all three notes, P4, ♭5, P5 — just be sure to end up anywhere but the ♭5! That is one of the quintessential sounds of the blues.

Fool around with bends, too. Try bending the P4 up to P5, then releasing slowly and picking the ♭5 on your way to P4.

Use it between other notes, too, not just the P4 and P5.

RT6a3 • Blue Note

Spend some time with this one. It shouldn't be a hardship.Blue note for navigation

In addition to sounding great, the blue note also aids with navigation. That’s why I’ve decided to introduce it so early.

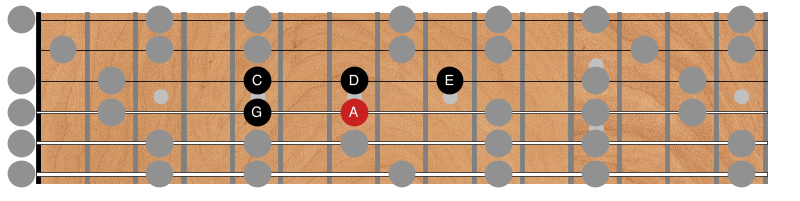

It was easy to keep your place when we looked at a single octave frying pan. Each note only existed in one place:

Fig 2. One-octave frying pan

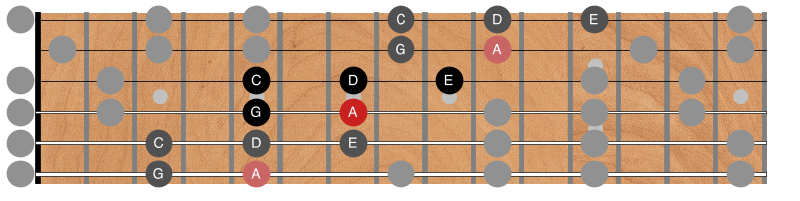

But you may have noticed yourself getting a little lost occasionally when we repeated that shape in three locations:

Fig 3. Three one-octave frying pans

It looks straightforward enough when the shapes are highlighted on a diagram like that, but when you’re navigating the (presumably unmarked!) neck of your own guitar it’s easy to lose track of which strings have three notes and which just two.

The difficulty is that everything looks somewhat similar: every note is a whole step away from another note on the same string. It’s extremely easy to confuse the ♭3 and the ♭7 at the far end of the pan, for example: was that the C or the G?

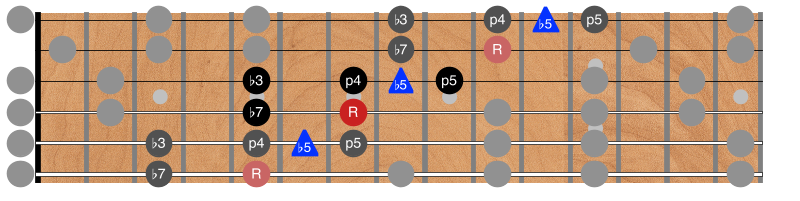

That’s why I recommend practicing your penatonic shapes with the blue note as much as possible. It breaks up the pattern of whole note intervals and gives your brain something to hang onto.

Fig 3. Frying pans with the blue note

The blue note provides both your muscle memory and your brain a “handle.” You know instantly, without conscious thought, that a group of three notes together is the P4, ♭5, and P5.

We still have several more chapters to go regarding the pentatonic scale. All subsequent pentatonic diagrams in this book will include the blue note.

You don’t have to play the ♭5 in your solos (that’s why it’s shown as an optional triangle rather than a circle). But I strongly, strongly recommend that you always practice your pentatonic shapes with the blue note included.

Practicing with the ♭5 helps you keep track of which note is which.