More pans

By now you should have realized that we can use octave shapes to move that frying pan shape anywhere we want.

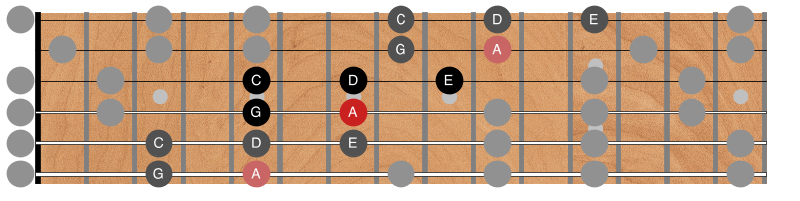

Let’s create two clones of our frying pan, one an octave lower and another an octave higher:

Fig 1. Pans above and below

Simply shift any licks you’ve already learned to these new locations to add some dynamism and energy to your solos.

You might start low and slow, for example, then move toward a climax where you start wailing with loud and fast trills in the highest pan. Listen again to familiar rock or blues solos for inspiration.

These shapes connect to one another. Instead of treating them as three disjoint shapes, create lines that fluidly move between them.

With practice, it takes very little mental effort to KNOW a priori which note you’re playing. Try to think about which note you are playing, not which part of the shape. It’s okay to think either in terms of note names (A/C/D/E/G) or scale degrees (R/m3/P4/P5/♭7) but always know what you’re playing!

The shape will help you navigate around the neck, though.

Do you see how the “heel” of the original pan (the root note A) butts up to the handle of the lower pan shape? The handle of the original shape (E) also butts up to the heel of the higher pan, except the tuning anomaly moves everything up a fret.

If you had more strings, the pattern would continue diagonally like that indefinitely, both higher and lower.

Practicing with the pans

Real drills are coming soon, but first just practice playing each “pan” in position, individually. Get your fingers used to finding the same five notes in a different location.

Next, try connecting the lower two pans. Do an ascending run from the G on the sixth string to the E on the third string, then descend back down. Play with these ten pitches (five notes in two different octaves) until you’re comfortable. The goal is to “see” both pans on the fretboard without effort.

Make certain you know which note you are playing at all times! Say the note names out loud as you play them (believe me, it helps). End your phrases on A as usual. You should find it liberating to have more than one octave to play with.

Now repeat with the higher two pans.

The best soloists play confidently and with intent. Try hard to aim for specific notes even as you move between pans. Know what you’re aiming for before you play it.

If it any point you aren’t completely confident how a note will sound before you play it, stop and reduce the number of “pans.”

Of course, you should also experiment a bit. If you stumble across something that sounds good, stop and analyze what you just played. Play it again. Write it down in your journal! Remember it for next time.

Once you’ve connected the upper and lower pairs, use the following exercise to practice playing with all three octaves:

RT6a2 • Pan Connection Drills

This proficiency test provides some mechanical drills to help you cement the locations for all these pitches into your brain.Pattern drills like these force you to visualize the shapes on the fretboard. They also help to improve technique, and prevent you from playing the same old licks and ascending/descending runs over and over.

Remember: you play what you practice. Try to make it musical.

The sound of each note

Now take a moment to repeat RT6a1 • Pan solos using all three octaves. Slowly play some lines (short sequences of two to seven or so notes from the Am pentatonic scale) over a single chord vamp (Am, or Am7). You’ll probably want to end the majority of your lines on the note A, but experiment by ending on different notes as well.

Develop a visceral feel for all the notes in the scale. Practice until you know how a note will sound before you play it.

To me, the notes sound as follows:

- Root (A)

- This is by far the most consonant sound. It feels like home. It sounds good, sweet, complete. Pure sugar.

- ♭3 (C)

- C evokes longing, or sadness. It fits over any Am chord (Am, Am7, Am9, Am13). It definitely belongs, but it emphasizes that minor/sad/savory quality. It reminds me of a sweet onion.

- P4 (D)

- D sounds slightly uncomfortable over an Am. The longer you hang on it, the more uncomfortable listeners become. It’s not wrong, exactly, but it feels like it wants to go somewhere else. Like thyme, it’s really great in moderation.

- P5 (E)

- E sounds almost as resonant as A. Not quite “home,” but it’s at least the front porch. It’s like adding MSG to the flavor of the root note: it makes it meatier.

- ♭7 (G)

- G Am sounds “cool” or “jazzy” to me. If the band is playing Am triads in the background, then G gives it that cool, jazzy, minor-seventh vibe. Technically, you are playing an Am7 when you play the G note over an Am triad! (Am7 comprises the notes A, C, E, and G). It’s like cinnamon – goes great with almost anything.

Be careful with D over Am (the P4), everything else is just compatible spices, but Am doesn’t contain a D, so you need to use it carefully. You probably don’t want to hang on a D too long. Unless you do! Sometimes a song wants that extra tension.

Note that these sounds/feelings/tastes change over every underlying chord. So far, we’ve only explored the sound over a single chord: the i7 (I minor seventh) chord.

The ♭3, for example, will sound very different over a I7. The half step difference between the ♭3 from the scale and the M3 in the chord tends to grate on the ears. As we practiced, simply “curling” or “tweaking” that C a bit toward the major 3rd relieves much of that tension.

A song in the key of Am might contain the chords Am7, Dm7, Em7 and E7. All five notes in the Am pentatonic scale will work over any of these chords since they are all in the key* of Am, but the sound/feeling/taste **changes** as the underlying chords change. That D note, for example, will sound sweet as sugar when the chord changes to Dm, for example.

Warning!

Anticipating chord changes is the hardest part of soloing!

The best solos play just the right note at the exact instant the underlying chord changes. This is incredibly difficult at first, but, as always, gets easier with practice.

Practice first with one chord vamps (e.g. Am7) as long as necessary. Only when you’re completely comfortable should progress to the remaining drills linked to below.

Learning to solo

Learning to solo over a complete 12-bar blues is hard. It takes hours and hours and hours and hours of practice.

As always, it’s best to break that practice into small, bite-sized chunks.

First recognize that most blues songs use Major chords!

A “standard” 12-bar blues often has the following chords:

I7 / % / % / %

IV7 / % / I7 / %

V7 / IV7 / I7 / V7

Those dominant-7th chords are all Major.

Minor blues progressions are much more varied, but a typical progression might look like:

i7 / % / % / %

iv7 / % / i7 / %

v7 / iv7 / i7 / V7

Those are all minor chords, except for the V7 in the last bar.

While the minor pentatonic scale definitely works over a major blues, I recommend starting with minor chords for your backing tracks.

I believe it’s best to first learn the sounds of a minor scale over minor chords. When you curl the m3 over i7, you’re adding tension (as opposed to releasing tension over a I7). It takes time to develop a feel for when and how to bend or curl notes. I find it easiest if most of the scale notes work “out of the box,” without adding any bends or curls.

So first get comfortable playing over just the i chord with RT6a1 • Pan solos.

When you are ready, proceed to the following exercises, but take your time.

For what it's worth

I’m always in too much of a rush to move on to new exercises. It’s easy to underestimate the degree of mastery required with each exercise. Keep at it until you can’t stand it any longer, and only then move to the next exercise.Soloing over a minor blues

When you’re ready, the first chord progression to explore is the i to the iv, and iv to i in a minor blues:

After a while, it should be obvious that the root note always sounds “best” over each chord (or at least “most resolved”).

The movement from a i chord to a iv chord (or back from the iv to the i) is extremely common. Listen to how each of the five notes sounds over each chord.

Notice how the note D sounds a bit out of place over Am. That’s because Am7 comprises the notes A, C, E, and G — but not D.

As soon as Dm comes around, though, that D note sounds particularly sweet. Playing D right as the chords change emphasizes the change. Nothing sounds more professional than playing solo notes that outline chord changes!

Pay attention to how the function of each note changes. In particular, note how the ♭3 of the i chord (C) becomes the ♭7 of the iv chord. One of the best ways to sound like you know what you’re doing is to emphasize thirds and sevenths in your playing. How does it sound to bend C up to D right as the backing track moves to Dm?

Remember to use different slurs and articulations. In particular, be sure to try curling the C when you’re over Am to add a little tension.

Playing over the changes

You’ve seen how just the five notes A, C, D, E, and G suffice to make coherent lines over a i-iv progression. Many careers have been made using just a single scale to solo over entire songs.

That’s not the only way to play, however.

Most “roots music” songs have just a single “key”. Some music styles like jazz have more complicated harmonies and key changes, but for the most part you can think about one key for an entire song.

That’s why it’s okay to play the Am pentatonic scale over both Am and Dm: both chords are in the key of Am.

Pro’s call this kind of one-scale soloing “playing over the changes.”

Playing the changes

There are at least two other strategies used when soloing over the iv chord (Dm), however:

You can think “key of the moment” and play Dm pentatonic instead (the notes D, F, G, A, and C). You play Dm pentatonic by moving the frying pan onto a higher string set, or by moving the shape five frets up the neck.

You can continue using Am pentatonic, but think about adding the note F. You add the note F to the frying pan by extending the “handle” one more fret. You’ll probably want to play F rather than E when playing over Dm.

Pro’s call these strategies “playing the changes.”

Note that Am pentatonic and Dm pentatonic are very closely related. They share the four notes A, C, D, and G:

Am pentatonic: A C D E G

R b3 4 5 b7

Dm pentatonic: A C D F G

5 b7 R b3 4

Playing the changes doesn’t require a dramatic shift in your note selection.

The two non-shared notes E and F are particularly interesting because they are only a semitone apart. Explore this in your solos to outline the changes. Try ending a phrase on E over the least beat of Am, then slide or bend it up to F just as the chord changes to Dm.

Now reverse it. End a phrase on F over Dm, then bring it down to E just as the chord moves back to Am.

Amazing how much difference a semitone can make, isn’t it?

Continue exploring the minor blues by examining the changes between the i and the v chord:

The last bar in a minor blues is typically a dom7 chord, which is a major chord. You’ll likely want to make different note choices when moving from or to the V7 than you would with the v:

Once you’ve explored the changes between each individual chord movement, you’re ready to tackle soloing over an entire 12-bar minor blues:

Soloing over a major blues

As we’ve discussed, most blues songs use dom7 chords, which are major chords.

We’ll need to learn about the major pentatonic scale before we can really tackle a Major blues.

Fortunately, it’s possible to play over a major blues progression using the minor pentatonic scale. Don’t be afraid to try some of your minor pentatonic licks over a major blues, but don’t set your expectations too high, either. We’ll get there soon.

We’ll get to major pentatonic scales eventually, but first, let’s take a closer look at the blue note.