Introduction

This is a very old video on triads that I really need to re-record:

Diatonic triads

While technically a triad can be formed with any three arbitrary notes, diatonic harmony is based on triads formed from stacked thirds: notes that are a major third or a minor third apart from each other in a diatonic scale.

To make a C Major triad, for example, you would play the notes C, E, and G simultaneously (skipping over D and F from the major scale).

Since there are two stacked intervals, and each interval can be either a Major 3rd (M3) or a minor 3rd (m3) there are logically four types of triads:

- Major

- root + M3 + p5 (a major 3rd between the first two notes, and a minor 3rd interval between the next two)

- Minor

- root + m3 + p5 (a minor 3rd between the first two notes, and a major 3rd between the next two)

- Diminished

- root + m3 + ♭5 (two minor third intervals stacked on top of each other)

- Augmented

- root + M3 + ♯5 (two major third intervals stacked on top of each other)

The first two (major and minor triads) are by far the most common and useful for playing songs.

Even big chords can be broken into triads

Harmonic theory doesn’t end with triads. Triads are two stacked thirds. If we continue stacking thirds on top, we get 7th chords (three stacked thirds), 9th chords (four stacked thirds), 11th chords (five stacked thirds), and even 13th chords (which contain all seven notes in the diatonic scale!).

Any of these larger chords can be reduced to combinations of simple triads.

If you played a Gmaj triad (G/B/D) at the same time someone else played a Bdim triad (BDF), for example, together you would make the sound of a G7 chord (G/B/D/F).

For some reason, this is rarely discussed, but you never need to play anything other than triads when accompanying other musicians, no matter how complex the harmony!

Major and minor triads

As we discussed in the introduction to this section, the C Major triad comprises the notes C, E, and G (skipping the intervening notes: D and F). It’s a minor 3rd interval stacked on top of a major 3rd.

The M3 interval between C and E is what gives the chord its “happy” sound. The third (major or minor) is what determines the “quality” of a chord. Major and augmented triads are classified as major, minor triads and diminished are minor.

C Major: C E G

- C

- root note of the chord.

- E

- M3 of the chord, a Major 3rd from C.

- G

- P5 of the chord, a minor 3rd above E, a perfect fifth from C.

By way of comparison, the C minor triad comprises the notes C, E♭, and G. The minor 3rd between the first two notes is what gives it the “sad” or “poignant” quality.

C minor: C E♭ G

- C

- root note of the chord.

- E♭

- m3 of the chord, a minor 3rd from C.

- G

- P5 of the chord, a Major 3rd above E♭, a perfect fifth from C.

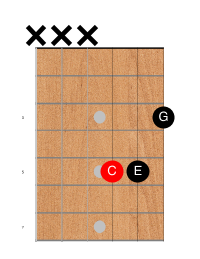

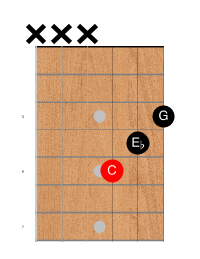

Here is one way to play the C Major and C minor triads on the top three strings:

Fig 1. C Major triad, root inversion

Fig 2. C minor triad, root inversion

As you can see, simply moving the 3rd (the middle note) down a fret changes the quality of the chord from major to minor.

You can create fingerings for diminished and augmented triads the same way. If you lower the G in a minor triad one fret to G♭ you create a diminished triad. Raise the G in the Major triad shape one fret to G♯ and you create an augmented triad.

Let’s continue with a more thorough look at the Major triad, though.

When the notes are ordered root, 3rd, 5th from lowest pitch to highest like this, we call it the “root voicing” or “root inversion” of the triad.

Voicings / Inversions

There are other orderings of the three notes besides the root inversion, of course. The six possible permutations of the three notes in Cmaj are:

- Close voicing:

- C E G (root inversion, with the root in the bass)

- E G C (1st inversion, with the 3rd in the bass)

- G C E (2nd inversion, with the 5th in the bass)

- Spread voicings:

- C G E (2nd inversion with the root dropped an octave)

- E C G (root inversion with the M3 dropped an octave)

- G E C (1st inversion with the P5 dropped an octave)

The first three of these groupings are called “close voicings” because the notes are as close together as possible. They can be played on adjacent strings, and are by far the more important ones to know.

The others are called “spread voicings” or “drop chord voicings” because one of the notes (voices) is lowered an octave. They can sound beautiful and are worth studying, but they can only be played if you skip a string (easiest with finger-style guitar).

We will ignore spread voicings for the remainder of these pages. Spread voicings are a more advanced topic that you might want to explore on your own.