Basic diatonic theory

To play guitar well, to play with intent rather than just memorizing patterns, you must be able to find notes anywhere on the fretboard instantly and effortlessly (get used to seeing those two words a lot on this site).

The goal is to “hear” any given sound in your head and intuitively know how to reproduce it on your instrument, without conscious effort. This takes years of practice, but it starts by learning where different notes are on the fretboard.

This really should be one of the very first things you learn on the guitar (along with some simple chord shapes and strumming patterns), but it is a surprisingly steep first step. It’s harder on stringed instruments like the guitar because the same note can be found in multiple locations along the neck.

Before you learn how to play the notes, though, you need to learn their names and how they work.

The first thing to realize is that there are only twelve unique notes in all of of western music. Not just hillbilly, but classical music, rock, and jazz, too.

Warning

This page is purely theory with no practice lessons. It’s also really long. It’s intended as introductory material that you’ll likely want to refer back to periodically.

To start learning how to actually find and play the notes on the fretboard, please feel free to skip this material for now and proceed directly to finding the notes. You can always return to this page later.

Shapes versus notes

A surprising number of guitarists never learn where all the notes are on the fretboard, much less how to read music. This is a real shame. Musicians learning almost any other instrument start by associating written notes on the staff with where and how to produce those notes on their instrument. It’s an odd quirk and unfortunate side-effect of a guitar’s layout that encourages students to think abut “shaps” rather than notes.

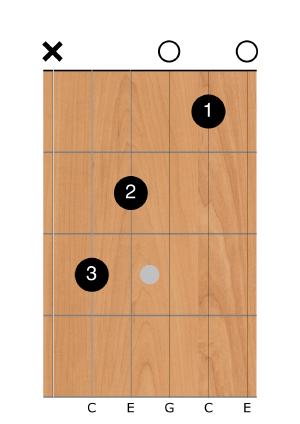

For example, the first thing millions of beginners learn to play is this C Major chord:

Fig 1. C Major in open position

They learn how to form this shape on the fretboard. They then associate this shape in their heads with “C Major”, along with different shapes for, say, “D Major” and “G major”. They think of this (often for years) as the only way to play a C Major chord.

But shapes aren’t music.

That diagram only shows one way to play a C Major.

As we will learn when we start studying chords and harmony, C Major is formed when you play the three notes C, E, and G simultaneously.

Figure 1 is just one way to play those notes. Plucking the notes individually from left to right (starting on the 5th string) the shape above sounds the notes C, E, G, C (again), and E (again). It’s those three notes that make this a C chord, not the shape.

Seriously, even small children learning piano can soon play a C major chord several different ways all over the keyboard. Literally millions of guitarists, though, never learn any way other than the diagram above, which is sad.

Shapes are unavoidable, though, and they aren’t all bad. You can’t learn guitar without memorizing shapes.

Shapes make it much, much easier for guitarists to play in different keys, for example. This is far more difficult on other instruments. A guitarist is much more likely to play in a horn player’s natural key (like F or Bb) than for a horn player to play in E, A, D or G (convenient keys for the guitar).

The musical alphabet

Its notes that create music, though. Not shapes. So what are the notes and where do they come from?

What follows is an over-simplified, highly condensed, and likely wrong history, but the concepts may prove helpful as we proceed.

I’ve already mentioned that all western music is comprised of twelve notes.

Seven of them are named after the first seven letters of the alphabet, A through G. Those are called the natural notes.

The remaining five are called accidentals, and get different names, like E♭ or G♯ (pronounced “E flat” and “G sharp”). Not every note can take a sharp or flat, though. Annoyingly, there is no note named “C♭” or “E♯".

I can already hear the first chorus of “why"s so I’ll attempt to answer the following common questions up front, with further discussion below:

- Why are there 12 notes, but only 7 get a letter?

- Because the most important scales in Western music, especially the Major Scale, have seven notes, with each note separated from the other by two different intervals (a whole step, or a half step). Following the same sequence of intervals, but starting on different notes leads to “in between” notes, the accidentals.

- Why do some notes have two names (like E♭/D♯)?

- Mostly because we want each of the seven notes in a diatonic key to be labeled A-G. The key of F, for example, comprises the seven notes F, G, A, B♭, C, D, and E. It would be weird to call the note A♯ instead of B♭ when playing a song in that key, as you’d have two “A” notes (the scale would become F, G, A, A♯, C, D, and E).

Also, sometimes you want to alter a chord for different textures. “The Hendrix chord,” for example, sharpens the 9th scale degree in the chord so it’s common to use ♯ if the 9th scale degree lands on an accidental.

- Why isn’t there a note called C♭ or E♭?

- See diatonic scales below. No matter which note you start on, you never need a note between B/C or between E/F.

- What does diatonic mean?

- Scales are comprised of two different types of invervals. Specifically, we call the intervals whole tone and a semitone. Diatonic literally means “two tones” (one whole, one half).

- On piano, why does the “white key” major scale start with the note C and not A?

- The over-simplied answer is that early music was mostly minor. The notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G can either be considered the A minor scale or the C Major scale.

Diatonic scales

In the earliest days of western music (think Gregorian chants) there were just seven notes. They were eventually named A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, but they could have been named John, Paul, George, Ringo, Larry, Moe, and Curly. They were just names.

Each note had its own pitch or tone, and each note in the sequence had a pitch that was higher than the prior one. The note B had a slightly higher pitch than A, and G was almost, but not quite, double the pitch of A.

Today, if you exactly double (or halve) the pitch of any given note, the resultant tone still keeps the same name. The tone produced at 440 Hz is called “A” but so are the tones at 880 Hz, 220 Hz, and 1760 Hz. They are all just the note “A”. (Read up on equal temperament if you’re curious about why this wasn’t always true.)

It’s important to realize that the pitches between each of the seven notes were not equally spaced. The spacing was originally based on integer ratios like 3:2 and 5:4 that were pleasing to the ear. The resulting tones were roughly the same as those produced by the white keys on a piano today, including a smaller interval between B and C, and between E and F than between any of the other notes.

The seven notes thus produced successively higher pitches, and repeated indefinitely: A B C D E F G A B C D E F G A.... This is why each sequence of seven notes is called an octave, by the way — the sequence repeats every eighth note.

This uneven spacing of seven notes eventually became known as a diatonic scale. It was called “diatonic” (literally “two tones”) because the distance between any two consecutive notes was either a whole step (a tone) or a half step (a semitone).

Today, a tone is exactly equivalent to two semitones.

On a guitar, playing one fret higher produces a note exactly one semitone higher. Play two frets higher and you produce a note a whole tone higher.

As we stated earlier, the sequence of whole-step / half-step intervals between each of the notes was fixed: there was a whole tone between every pair of notes except between B and C and between E and F which were separated by a semitone.

Starting on C, there is a whole step to D, another whole step to E, a half step to F, whole steps from G to B, then another half step to the next higher C where the sequence begins again.

We call the characteristic sound or feel of this specific ordering of tone

intervals (W W h W W W h) the major scale.

Literally all of western music derives from the major scale. It should have been promoted to General by now. Memorize that pattern: W W h W W W h.

Modes

If we start on A rather than C, though, the intervals become: W h W W h W W.

We call the character or feel of this sequence of intervals minor or

Aeolian mode. We can create a total of seven different interval sequences by

starting on different notes.

We call these different sequences of whole-tone and half-tone intervals modes. The first and most important mode (the Major scale) is obtained by starting on C. It’s also called Ionian mode.

If you start with G, you get Mixolydian mode (a great mode for soloing over the blues today, but I’m doubtful that any Gregorian blues chants survive).

Starting with different notes results in seven different modes — for precisely the same collection of seven notes.

It turns out that just by emphasizing one specfice note (the “key”) in the collection you can make music with very different “feels” even though you’re still using exactly the same notes.

You emphasize a note by playing it more often, ending phrases on it, and, most importantly, letting it continue to ring out under the other notes you play (this is called harmony). Technically, these are all forms of “implied harmony”. Modes are a harmonic concept, but they are why we have twelve notes today instead of just seven.

Emphasize the note C, and the notes A B C D E F G sound “Ionian”. Emphasize D and it sounds “Dorian”. And so on.

Eventually, somebody thought: “But what if I want to produce (say) that sweet, sweet Ionian sound, but emphasizing the note G instead of C?”

In other words, they wanted a group of seven notes that starts on G, but followed the W W h W W W h interval sequence of Ionian mode.

That would require the notes: G, a whole-step to A, whole step to B, half step to C, whole step to D, whole step to E, but then we need a whole step to … what? F is too close (only a half step from E) and G is too far away.

They needed a note halfway between F and G for it to sound Ionian instead of Mixolydian. Since this note replaces F in the sequence, they called it F♯. It’s just another name, but for a new note that didn’t exist before.

It turns out that if you go through the process of creating every mode starting on each of the seven original notes, you’ll end up needing five total of these “halfway” notes (one between A/B, C/D, D/E, F/G, and G/A).

You’ll end up with only twelve notes in total. Today, we call these twelve notes the chromatic scale:

The chromatic scale.

- A

- A♯ or B♭

- B

- C

- C♯ or D♭

- D

- D♯ or E♭

- E

- F

- F♯ or G♭

- G

- G♯ or A♭

Even today we only have twelve unique notes: the seven natural notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, and the five accidentals, A♯/B♭, C♯/D♭, D♯/E♭, F♯/G♭, and G♯/A♭.

Here, for example, is how you would construct the Major scale (AKA Ionian mode or the interval sequence W W h W W W h) for each natural note key:

The Major scale notes

C Ionian: C D E F G A B (no sharps or flats)

G Ionian: G A B C D E F♯ (one sharp)

D Ionian: D E F♯ G A B C♯ (two sharps)

A Ionian: A B C♯ D E F♯ G# (three sharps)

E Ionian: E F♯ G♯ A B C♯ D♯ (four sharps)

B Ionian: B C♯ D♯ E F♯ G♯ A♯ (five sharps)

Following the W W h W W W h sequence to derive F Ionian, though, we start with F, whole step to G, whole step to A, and then we need a note between A and B. We’re replacing the note B, so this time we call it B♭, not A♯:

- F Ionian: F G A B♭ C D E

You can also create major scales for “between” note keys (i.e. the accidentals like B♭).

Yup. The B♭ Major scale really is a thing, for example. No further new notes are required, but you’ll start using the ♭ names for the accidentals more often.

These “in between” notes have two possible names, which can be confusing. The rule is simple, though, just use the name based on what you’re replacing. For G Ionian we replaced F so we called it F♯ and not G♭.

There are seven total modes, not just Ionian. In addition to the interval sequence, it can be helpful to think about how each mode differs from Ionian (the major scale):

The modes

| Mode | Interval sequence | Changes from Major scale |

|---|---|---|

| Ionian | W W h W W W h | (none) |

| Dorian | W h W W W h W | ♭3, ♭7 |

| Phrygian | h W W W h W W | ♭2, ♭3, ♭6, ♭7 |

| Lydian | W W W h W W h | ♯4 |

| Mixolydian | W W h W W h W | ♭7 |

| Aeolian | W h W W h W W | ♭3, ♭6, ♭7 |

| Locrian | h W W h W W W | ♭2, ♭3, ♭5, ♭6, ♭7 |

Note function

The names of notes are absolute. They never change, no matter what scale, melody, or chord you’re playing.

C is always called C. The note D is always called D (and can always be found two frets higher than any C on the fretboard).

Remember that the twelve note names are just names. The names are simply an accident of history. They could have been named after the twelve apostles or the first twelve letters of the Greek alphabet.

In some ways, it would have been nice if they had been: things get confusing when we start talking about how the notes function in different contexts.

It’s admittedly confusing that the accidental notes have two names, but they are just single notes. G♯ and A♭ are two names for the same note, for example. That note will always be called by one of those names, no matter the context.

The function of a note, however, is relative and changes depending on context. Because function naming also uses sharps and flats, this can be confusing to say the least!

Functional names differ from the absolute name of a note. This confuses the heck out of everyone when they first start studying music.

Scale degrees

One functional name for notes are scale degrees. Scale degrees are numbered relative to a given note (known as the “root” of the scale) and the type of scale. Scale degrees change depending on which note is considered the root of the scale.

Remember this!

Note names use letters and never change. Functional names like scale degrees and intervals change depending on context but always use numbers. Both use sharps and flats.

Sharps and flats precede numbers, but follow letter names.

You’ll eventually become accustomed to saying and parsing sentences like: “The ♭7 of C Mixolydian is B♭.”

The C Major scale, for example, comprises the seven notes C, D, E, F, G, A, and B in that order. C is the root note and 1st scale degree. D is the 2nd scale degree, E the 3rd, etc.

If someone says “play the ♭5” and you are playing in C Major, they are telling you to play the note G♭ (“the 5” or the 5th scale degree, flattened by one semitone).

This is only for the key of C Major, though! The note “G” is only the 5th scale degree in the key of C. If we were in the key of A minor, we would call G the minor seventh (or ♭7 sometimes written as m7) scale degree. The scale degree depends on the key.

Intervals

Intervals are the other functional name for notes. An interval is the distance between pairs of notes. The interval from the note C up to the note D, for example, is called a Major 2nd.

Unfortunately, interval names confuse people for several reasons:

The interval between the same two notes depends on which note is higher in pitch. C up to D is a Major 2nd, but D up to the next higher C is a minor 7th.

Confusing things even further, guitarists often move notes into different octaves to simplify fingering: technically, a note moved to a lower octave might become a minor 7th, but it’s common to still think of it as a Major 2nd.

Actually, even that’s a lie. When we start discussing harmony, specifically extended chords, the extended notes are in a higher octave and called 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths instead of 2nds, 4ths, and 6ths. That note in point 2 is more commonly called the “9th” rather than the “2nd”.

Some intervals have multiple names. Just as F♯ is also known as G♭, the interval from C to the note F♯/G♭, for example, can be called an “augmented 4th” or a “diminished 5th” depending on context. To confuse you even further, that specific interval is also known as a “tritone” and is nicknamed “the blue note” as well as “the devils interval” (diabolus in musica).

Sadly, interval naming is just a mess. The names do tend to work in practice, but occasional confusion is unavoidable. When in doubt, use the absolute note name!

Here is the name of each interval relative to the note C:

Interval Names

| Note Name | # Frets from C | Interval name(s) from C | Interval up to higher C |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 0 | Unison | Octave |

| C♯/D♭ | 1 | minor 2nd (m2) | Major 7th (M7) |

| D | 2 | Major 2nd (M2) | minor 7th (m7) |

| D♯/E♭ | 3 | minor 3rd/augmented 2nd (m3/+2) | Major 6th (M6) |

| E | 4 | Major 3rd (M3) | minor 6th (m6) |

| F | 5 | perfect 4th (p4) | perfect 5th (p5) |

| F♯/G♭ | 6 | augmented 4th/diminished 5th/tritone (+4/-5) | augmented 4th/diminished 5th/tritone (+4/-5) |

| G | 7 | perfect 5th (p5) | perfect 4th (p4) |

| G♯/A♭ | 8 | minor 6th/augmented 5th (m6/+5) | Major 3rd (M3) |

| A | 9 | Major 6th (M6) | minor 3rd/augmented 2nd (m3/+2) |

| A♯/B♭ | 10 | minor 7th/augmented 6th (m7/+6) | Major 2nd (M2) |

| B | 11 | Major 7th | minor 2nd (m2) |

| C | 12 | Octave | Unison |

Notes:

You can mostly ignore the last column in that table, but it’s worth knowing that the minor/major “quality” of an interval flips when going up to the next higher root. It’s also worthwhile to know the numbers always add up to 9 (e.g. minor 3rd / Major 6th depending on direction).

The exceptions are the “perfect” intervals, the 4th and 5th. They are neither major nor minor, so the quality doesn’t flip no matter which direction you go.

Flattening a perfect interval produces a “diminished” interval, but flattening a Major interval makes it minor, not diminished.

Sharpening a minor interval makes it major.

Sharpening Major or perfect intervals makes them augmented.

The tritone of F♯/G♭ is exactly halfway between Cs in two different octaves. It’s the only interval that stays the same whether you coming up from a lower C, or going up to a higher one. It’s this unbalanced, neither here nor there, nature that gives it its “blue note” quality.

To net it out, here are the various names of the natural notes that make up the C Major scale (these are the white keys on a piano):

The C Major scale

| Note | Scale Degree | Steps from root | Interval from C |

|---|---|---|---|

| C (root) | 1 | 0 | Unison |

| D | 2 | W = 2 | M2 |

| E | 3 | WW = 4 | M3 |

| F | 4 | WWh = 5 | p4 |

| G | 5 | WWhW = 7 | p5 |

| A | 6 | WWhWW = 9 | M6 |

| B | 7 | WWhWWW = 11 | M7 |

| C* | 8 | 12 | Octave |

| D* | 9 | 12 + W = 14 | Major Ninth |

| F* | 11 | 12 + WW = 16 | Major Eleventh |

| A* | 13 | 12 + WWhWW = 21 | Major Thirteenth |

Notes:

Extensions (beyond the first octave) are marked with an asterisk. Piano players usually keep the extensions in a higher octave, but guitarists often move notes to any convenient octave. They may think of D’s in a lower octave as “ninths,” for example, because of fingering restrictions.

In practice, you won’t always think about steps up from the root. You might think “B is the Major 7 in the C Major scale,” for example, but when you go to play it, it’s a whole lot easier to find “down a fret from C” than “up 11 frets from C”.

Similarly, nobody thinks “up 14 half steps” to find the 9th! Instead, we think “two frets above the root”(since the 9th scale degree is the same note as the 2nd, the 11th the 4th, and the 13th the 6th).

When we get to chords and harmony, we’ll see that we create chords by “stacking thirds” (taking every other note). CMaj contains the notes C E G. CMaj7 = C E G B. CMaj9 = C E G B D. CMaj11 = C E G B D F (in theory). CMaj13 = C E G B D F A (in theory — that’s all seven notes in the scale!). The reason there are no 10/12/14 scale degrees is because those notes are already present in the underlying, non-extended chords. You wouldn’t call an E in a higher register a “10th,” it’s still a Major 3rd relative to C, no matter what octave its in.

So if, for example, you were playing a song in the key of C Major, you could refer to the note E as “the third of the scale,” or “the major 3rd.".

Chords use numbers too

One final source of much confusion: the chords associated with a key also use numbers and major/minor/diminished/augmented terminology. Chord numbers are usually written with roman numerals, but the distinction between “the 4” and “the IV” can be difficult to hear!

The key of C Major comprises the notes C D E F G A B but it also comprises seven chords (or “triads”):

| Chord name | Notation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| C | I | C E G |

| Dm | ii | D F A |

| Em | iii | E G B |

| F | IV | F A C |

| G | V | G B D |

| Am | vi | A C E |

| Bdim | vii° | B D F |

So the chord F (Major) for example, is called the IV chord, and the note F is the 4th degree of the scale.

By convention, we use upper case roman numerals (I, IV, etc.) for major chords, lower case roman numerals (ii, vi) for minor chords. This is sometimes called “Nashville notation.” Arabic numerals (1, 3, 5, etc.) are always used for notes/intervals/scale-degrees.

This helps considerably in written material, but not at all when speaking. It’s up to the listener to figure out if people are talking about chords or notes.

Here’s a totally made up band discussion, for example:

Guitar: I really like the sound of a minor 9th on the “two” (ii) chord here.

Translation: adding the note E to Dm sounds cool.

Bass: You want me to hit the 9?

Translation: Shall I play an E?

Guitar: Nah, I’ll put it on top. Riff on the third instead.

Translation: Emphasize the note F instead.

Drummer: You’re both rushing, tighten up.

Translation: I need a beer.

Believe it or not, all of this will eventually make sense.

Next: Finding notes